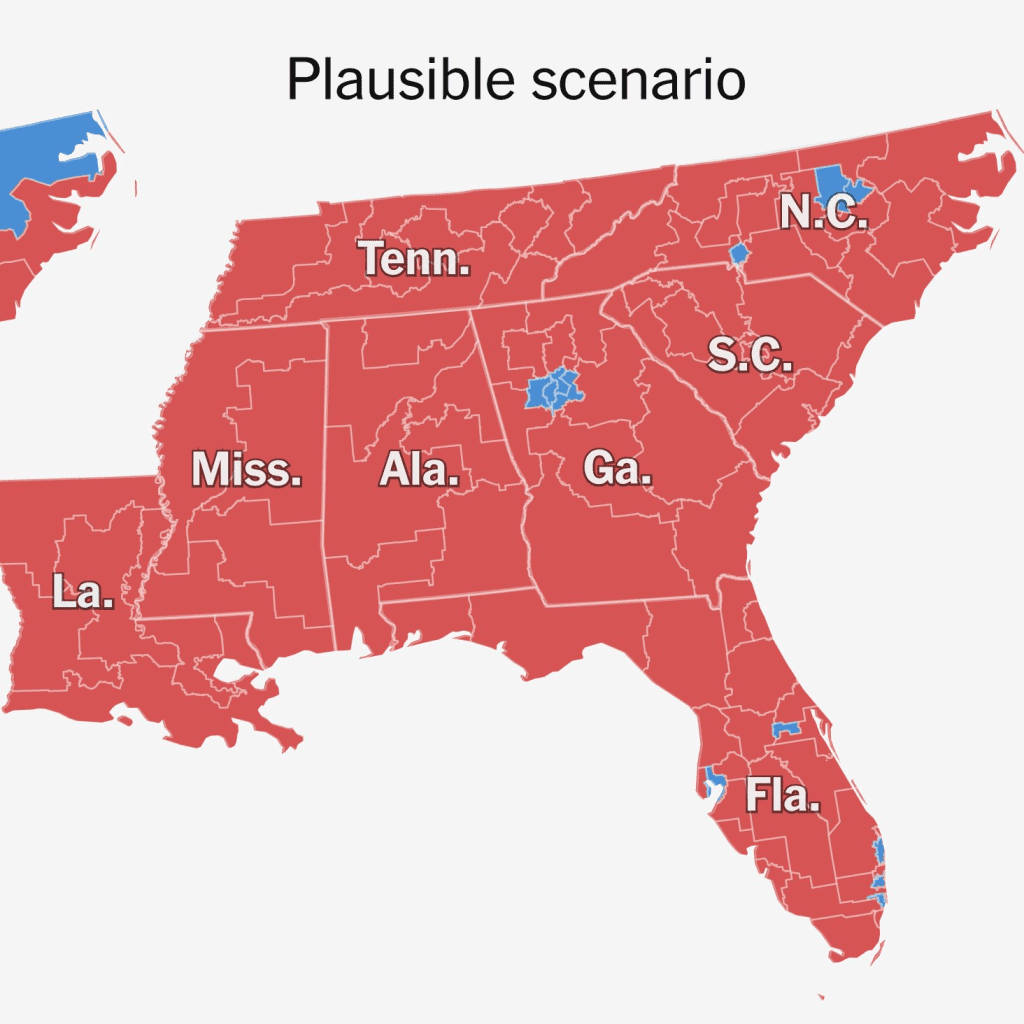

With the Supreme Court of the United States poised to curb race-based district protections, Southern Republican-led states prepare massive mid-cycle redistricting that could net the party nearly 20 extra House seats

A seismic shift in America’s electoral battleground is quietly unfolding across the Deep South. In states such as Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia, Mississippi and Texas, Republican legislatures are gearing up for what could become the most consequential redrawing of congressional maps since the post-census era — and they’re doing it ahead of the 2026 midterm elections. At the heart of this push is the possibility that the Supreme Court will substantially limit the reach of race-based protections under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), thereby opening the door for partisan map-makers to redraw lines with fewer legal restraints.

The strategy is clear: by leveraging a redrawn legal framework, GOP-controlled states hope to convert districts once drawn principally under race-based criteria into more reliably Republican seats. Publications exploring the issue suggest that the party could gain nearly 20 additional U.S. House seats if the legal environment shifts. This effort reflects the direction urged by former President Donald Trump, who has repeatedly encouraged sympathetic state legislatures to redraw maps now, rather than wait for the next decennial cycle. Analysts at Reuters note that the Trump-era dominance is manifesting not just in rhetoric but in a mid-cycle redistricting push rarely seen outside traditional census timing.

One of the most immediate flashpoints is the case of Louisiana v. Callais (consolidated with Robinson v. Callais), which was re-argued before the Supreme Court in October 2025. The Court’s conservative majority appears likely to narrow Section 2 of the VRA — the provision under which many majority-minority districts were created — and that has the potential to reshape power in southern states where those districts have historically been drawn to bolster minority representation. Constitutional law observers warn that a ruling constraining Section 2 could release Republican-led states from frequent lawsuits and regulatory oversight, enabling more aggressive remapping efforts.

In neighboring states, the trend is already in motion. For example, the Republican-led legislature in North Carolina has approved a new U.S. House map in October designed to flip a Democratic-held district, clearly aligning with the Trump-backed strategy to safeguard the GOP’s congressional majority. And in Texas, new maps aim to capture five additional seats, pending legal challenge in federal court. Across the South, state capitals are quietly briefing lobbyists and setting up the legislative mechanics for these redraws.

The implications for democracy are significant. Civil-rights groups warn that weakening the VRA could lead to suppression of minority electoral power and a rollback of decades of hard-won voting protections. They argue that these changes are less about fairness and more about partisan advantage. On the other hand, Republican strategists contend that these redraws merely reflect demographic changes, partisan shifts and the end of what they describe as an outdated enforcement regime from Washington.

What remains uncertain is how voters will react. While the map-makers may act behind closed doors, the resulting districts will determine — for years — the shape of representation in key states. If the GOP succeeds in flipping multiple districts, it could not only stabilize its House majority but also redraw the national political map in its favor. For those watching Washington, this moment may mark the beginning of a new era where electoral maps are redrawn not just after a census but as ideological tools in the fight for legislative control.

For now, the redistricting machinery hums in statehouses across the South, guided by legal shifts at the highest court and the strategic urgency of an emboldened Republican Party. The 2026 midterms may yet hinge not just

on campaigns and candidates — but on how the lines are drawn before voters ever cast a ballot.

WOW! Southern GOP states are now preparing to REDISTRICT their Congressional maps in the event Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and conservatives at the Supreme Court END race-based VRA districts

WOW! Southern GOP states are now preparing to REDISTRICT their Congressional maps in the event Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and conservatives at the Supreme Court END race-based VRA districts